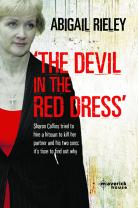

The selection of the jury in the case of Rex v O’Cioghly Armagh, 1798 Image from Findmypast.co.uk © Crown Copyright Images reproduced by courtesy of The National Archives, London, England

Over the years I’ve sat through a lot of jury panels. I remember Monday mornings in the Central Criminal Courts in Dublin when Mr Justice Paul Carney would oversee the selection of the juries for the trials that were due to start. Court 4 would be jammed and stifling hot, whatever the season, as jury panellists, various accuseds, victims’ families, barristers, solicitors, gardai and journalists all jostled for elbow room in the body of the court. Carney would often arrive late and was brusque with the excuses of panellists who were reluctant to do their civic duty. The selection process takes time, each person called has a chance to excuse themselves and both prosecution and defence teams have the right to reject anyone they don’t feel will be sympathetic. In a modern trial, they don’t say that reason out loud so you have no way of knowing if you’re on that jury panel if you have been rejected because your hair was too long, too short or some unconscious expression observed by the barristers has convinced them that you will behave in a certain way.

Panellists are also asked if they have any connection to the trial that they could be selected for. If they live near the place where the crime took place, know the accused or the victim or their families, have strong views about the case in any way. Of course, there’s no guarantee that a jury member will always confess a bias but the extraordinary thing about juries is that, whatever their makeup, once they are twelve, and once they have retired to their room, they tend to take things very seriously indeed. Paul Carney’s jury panel sessions were a tradition in themselves. Each week he would issue the same warnings, threaten the same threats of the consequence of not being straight. He would be sympathetic to students with upcoming exams but less so with executives or those in the financial services who would not do their duty. There was a formula to the process and perhaps this was what shapes the juries into the entities they become.

I’ve written a lot about the trial of William Bourke Kirwan, an artist who killed his wife Maria on Ireland’s Eye off the coast of Dublin in 1852. You can read about the case in more detail in posts here, here and here. In that case, the jury actually felt the need to defend their position in a letter to the press. Even though I’ve seen some pretty odd and occasionally downright mad decisions by juries over the years, I’ve never seen a case where they would feel the need to justify their decision. The only exception would perhaps be the Eamonn Lillis case, subject of my second book, Death on the Hill, where the jury explained exactly how they had come to their decision of manslaughter and, possibly because they felt there might be speculation, were absolutely specific that they had decided Lillis was guilty of manslaughter because the prosecution had not proved the case for murder.

Juries interest me, and I’ve often wished I could sit on one simply to see things from the other side, so there’s one record set among the UK National Archives crime records that fascinates me. It’s a little bit outside my period – I usually research Irish courts between 1830 and 1860 or so – but it’s one I keep going back to. It’s a ledger hidden in the rather prosaically named HO130 collection, basically the 130th box of the Home Office records. The fact that it exists I still find amazing. It’s a little piece of colonial history and an insight of how things are done after a rebellion. In these dark times we are living in, perhaps it’s an insight that’s useful to have…

The jury selection was for the trial of United Irishman Father John James O’Cioghly of Loughgall, in County Antrim. Father O’Cioghly and others were on trial for their part in the rebellion of 1798. The jury panel was made up of landed gentry. There were no reluctant students or bankers in this lot. What’s so extraordinary about this record is that it is a record of the silent discussions I watched every Monday in Court 4 in front of Judge Carney, the decisions by prosecution, defence and the magistrate himself on each individual juror. This seems to be a document that was never meant for outside viewing. Justifications for people’s suitability or not are blunt and sometimes brutal.

Take number 22, Sir Richard Glode, for example. The notes comment that Sir Richard should be enquired about. He was strongly anti-aristocratic and this was possibly because he was “exceedingly low born” even if he didn’t show it.

Image from Findmypast.co.uk © Crown Copyright Images reproduced by courtesy of The National Archives, London, England

John Farnaby was not to be trusted. One of the comments notes that he had recently taken his wife’s maiden name of Lennard (sic) – almost certainly the Irish surname Leonard. He was definitely for the cause of a united Ireland.

Image from Findmypast.co.uk © Crown Copyright Images reproduced by courtesy of The National Archives, London, England

Farnaby might have been tainted by marriage but George Russell had no such excuse. He was “one of the worst of the panel” according to the notes, having actually given £500 of his own money to the United Ireland cause.

Image from Findmypast.co.uk © Crown Copyright Images reproduced by courtesy of The National Archives, London, England

Luckily for the Crown, eager to make sure O’Cioghly and his compatriots served as a warning, there were also men like Robert Jenner who, the notes reassure, “if eleven would acquit, he would convict.”

Image from Findmypast.co.uk © Crown Copyright Images reproduced by courtesy of The National Archives, London, England

The jury selection for the case of Rex v O’Cioghly is a rare insight into how a jury is selected, or in this instance possibly stacked. I’m always amazed that such things survive but the historian in me is delighted they do. The journalist in me is equally delighted as this is an insight, however much removed, of a part of the story I could never observe. I’ve been unable to find a trial report for the O’Coighly trial as this was a time when Irish journalism was in its infancy and most newspapers did not yet cover Irish news. Either the jury was well stacked or the Crown’s case was watertight though as Father O’Cioghly was executed on June 7, 1798.

Leave a Reply