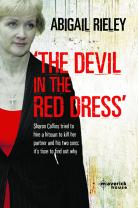

Lon Chaney as the master detective Edward C. Burke in the film London After Midnight, which allegedly frightened a man to commit murder. Image thanks to Doctor Macro.

It’s been a while since I’ve told the story of a trial. Hardly surprising since that’s not what I do anymore but I haven’t moved very far away from that line of work really. I still spend far too much time immersed in the details of murders and murderers so I’ll continue to share their stories.

When I was growing up Kubrick’s Clockwork Orange was notorious. We all knew it was banned, and unlike the so-called video nasties that were our favourite loans from the video store, it had been withdrawn by it’s director after being linked to violence.

But 50 years before Clockwork Orange was linked to violence a sad little case came before the courts in London that had a similar link to Hollywood. It went largely unreported by the London papers, unsurprisingly since the case had that familiar ring that even now made it unlikely to generate many column inches. A woman killed by her partner. I’ve covered so many down through the years and written about them here. But what this case extraordinary was the defence – that the accused man had been so terrified by a film he’d recently seen, London After Midnight starring Lon Chaney, that he had lost his mind, albeit temporarily.

On October 25th 1928 the Exeter and Plymouth Gazette announced the “Hyde Park Tragedy”.

The following day the Dundee Evening Telegraph carried a report from the inquest. An unnamed constable described finding the young Irish woman. She was lying huddled, face down with her left hand on her throat. Her glove was saturated with blood.

Patrick Mangan, her brother, told the inquest that his sister had been seeing Williams for three weeks. He had once had to throw him out of her place for being drunk.

Williams was expected to be discharged from hospital in about 10 days time. A picture was beginning to form. The inquest was adjourned until he could be questioned.

In November the case came before the Marlborough Street Police Court. This was the first time details of the case had been heard in public. The Nottingham Evening Post informed it’s readers that 21-year-old Julia had been employed as a worked as a house-maid in a house on Stanhope Gardens in South Kensington.

The police doctor said that considerable violence must have been used to cause the wound in her neck. A policeman who had gone to charge Williams in hospital told the court that before he could caution him Williams had told him “I did it, she had been teasing me.”

A couple of months later the case came for trial in the Old Bailey. The Central Criminal Court after trial calendars show that Williams was charged on two counts. One of murder, the other of suicide.

I can’t tell how widely reported the case was. I haven’t been able to find a single reference in the London papers, although this is probably down to the late (for digital archive sources) date, but there was quite a bit of coverage north of Watford, as my mum used to say.

The Hartlepool Mail on December 20th 1928 carried a report from the Central Criminal Court, Williams was being tested to see if he was fit to stand trial. He was indicted on the charge of murder and pleaded not guilty but a key medical witness was not available to back up his insanity defence. Williams took the stand and told the court that he had known Julia Mangan for around a month. He had wanted to kill himself three days before he had killed Julia, on October 23rd. He had put a cut throat razor in his pocket. He had not intended to hurt Julia, they were friends. He had wanted to marry her, although he had told her a false name when they first met.

There had been no quarrel he said. “I felt as though my head were going to burst and that steam was coming out of both sides. All sorts of things came to my mind. I thought a man had me in a corner and was pulling faces at me. He threatened and shouted at me that he had me where he wanted me.” The man, it appears, was Lon Chaney as he had appeared in London After Midnight, a film Williams had seen several months before.

The defence put forward their case. A local chaplain from Williams’ home town of Caernarvon told the court he knew of five separate incidences of insanity in Williams’ family. A London doctor said that while he had treated Williams for neurasthenia and would have considered him “abnormal” he would not have certified him insane.

Dr James Cowan Woods, described as a lecturer on mental diseases, suggested that Williams had been suffering from an epileptic mental attack, “epileptic automatism”, much to the consternation of the judge. “You have said that many people of high intelligence are going about their work, although they are suffering from epilepsy. Are you suggesting that they might commit murder tomorrow?”

But by the time Williams stood trial in January there was still some confusion about whether he suffered from epilepsy at all. No firm diagnosis was given during the trial according to the available reports. The Western Daily Press was more focused on the Hollywood angle, as it appeared was the trial judge, Mr Justice Humphries, when he was summing up to the jury.

“I do not know whether you have been to see any film in which Mr Lon Chaney acted. One of them, we are told is The Hunchback of Notre Dame, and another London After Midnight. If any of your members of the jury have seen the later, or even the advertisements of what Mr Lon Chaney looks like when he is acting in that film you may agree it is enough to terrify anyone.”

The film in question, directed by legendary director Tod Browning best known for his later films Dracula (1931) and the infamous Freaks (1934). It is known as the director’s first exploration of the vampire theme and is one of the most famous lost films – the last known copy was destroyed in a fire at MGM studios in 1967. Chaney plays a detective intent on discovering who killed Sir Roger Balfour. It was based on a short story written by Browning, The Hypnotist. Chaney, was already famous for his skills of makeup and one of the selling points of the film was that the audience got to see the master at work as the detective dons various elaborate disguises – including the famous one shown in the poster and the still at the top of this piece – with sharpened teeth and special wire fittings like monocles to give him that special hypnotist stare. The film was rather a flop.

However, during Judge Humphries obviously wasn’t a fan of such popular entertainment and was only going by what had been said in court.

Williams was found guilty and sentenced to death. Judge Humphries instructed that further inquiries were made by the Home Office to try to get to the bottom of that epilepsy diagnosis. I never did find out if he was executed or not.

So the case became part of the legend of a legendary film. Personally, having gone through all the newspaper reports while I was researching this I’d have my doubts about Williams’ story. The story at the heart has too many similarities with cases I’ve covered in the past. There’s Williams’ hospital statement, that he killed her because she made fun of him. Had he proposed and been turned down? Had she broken things off? These would be far more likely scenarios in cases where women are killed by their intimate partner. I’ve also covered cases where the medical evidence was in no doubt, where the accused could not be found guilty by reason of insanity. Those cases are so often marked out by the degree of violence. While the evidence is there that the wound to Julia Mangan’s neck was done with violent force there isn’t the overkill that so often goes with a psychotic break – and I’m not even getting into the whole epileptics as killers undercurrent to the evidence…that seems more like common prejudice than anything that would be born out by modern medicine.

References:

- Exeter and Plymouth Gazette, 25 October 1928, page 8 of 8

- Dundee Evening Telegraph, 26 October 1928, page 6 of 12

- Derby Daily Telegraph, 13 November 1928, page 7 of 12

- Hartlepool Mail, 20 December 1928, page 10 of 10

- Western Daily Press, 11 January 1929,page 11 of 12

- Central Criminal Court: after-trial calendars of prisoners (TNA Ref: CRIM 9)

All sources found on Findmypast